Recently at a pathology conference, I met my friend (and former colleague), who has an advanced background in mathematics and computer science. I have previously worked with him on several image analysis and artificial intelligence digital pathology projects. After an interesting lecture given by a recognized pathologist and scientist in the digital pathology field, my friend approached me and said:

“Please, tell the pathologists not to use uncorrected p-values from studies in which multiple parameters were tested”.

He asked me to spread this request in the pathology community, because I am a pathologist, and it will be nicer and more readily accepted coming from a peer.

Immediately I thought:

“oh no, have I also made this mistake recently, and could he actually be referring to me, and not to the lecturer we just heard?“

but no, that couldn’t be the case, I would not dare nor have the chance to perform statistical analysis for any of the projects I have worked on….Uff, it was not about me…(this time), it was about others…” those people who know just enough about statistics to be dangerous”. Well, then I can totally pass the message (I thought to myself, secretly relieved that I was not caught redhanded)!

As I am not at all proficient in statistical analysis and was lucky enough to have this part of my research taken care of by specialists, I decided to broaden my horizons, investigate the problem and point out the most common statistical mistakes done by pathologists. The problem turned out to be more complicated and omnipresent than I thought, and I encountered many publications and other resources addressing it, some of which I will cite in this post.

Statistical ignorance in biomedical research

Already such journals as “The Economist” and “New Scientist” have written about it.

According to these and other sources, as much as half of the biomedical publications may contain statistical mistakes, including:

- inadequate choice of methods,

- inadequate study design,

- wrong graphical representation of the results, among others.

Here are citations from a few of the publications on this subject:

“Standards in the use of statistics in medical research are generally low. A growing body of literature points to persistent statistical mistakes, flaws, and deficiencies in most medical journals” Strasak et al. (2007)

“Amazingly, it is widely considered acceptable for medical researchers to be ignorant of statistics. Many are not ashamed (and some seem proud) to admit that they ‘don’t know anything about statistics’. “Huge sums of money are spent annually on research that is seriously flawed through the use of inappropriate designs, unrepresentative samples, small sample [sizes], incorrect methods of analysis and faulty interpretation.” Douglas Altman (1994)

I am no better…

Unfortunately,

I (and I believe many other pathologists as well) am guilty of this kind of ignorance.

Statistics constituted a very small portion of my pathology education. This is not an excuse, I should know more, but I also realize, that this is not an area of my expertise, and as in any other area outside of my expertise, I reach out to specialists for help, as they reach out to me for pathology interpretation. It’s great to have a working knowledge of subjects outside of your own domain, but

you shouldn’t be fooled into thinking that you can do without the experts.

Having worked in drug development, a very multidisciplinary field, I learned that in multidisciplinary teams experts in different disciplines contribute to the projects, and not always does one fully understand the entire extent of their contributions. The key to success is to work together and involve the necessary expertise at the beginning of the project. This should apply to any kind of research, to provide reliable results and comprehensive conclusions. So,

if you are a pathologist including statistical analysis in your work or research, please involve a statistician.

This will not only let you focus on your area of expertise but will also provide quality results and correct interpretations of an important part of your research which is not your main focus.

My two statistic lessons

From the brief discussion with my friend during the conference coffee break I learned about two most common mistakes. They may seem obvious to many of you, but I believe there are still enough pathologists and researchers who would benefit from my basic explanation. By no means do I want to provide statistical advice here, and I will point out a good resource later, but I would like to raise everyone’s awareness.

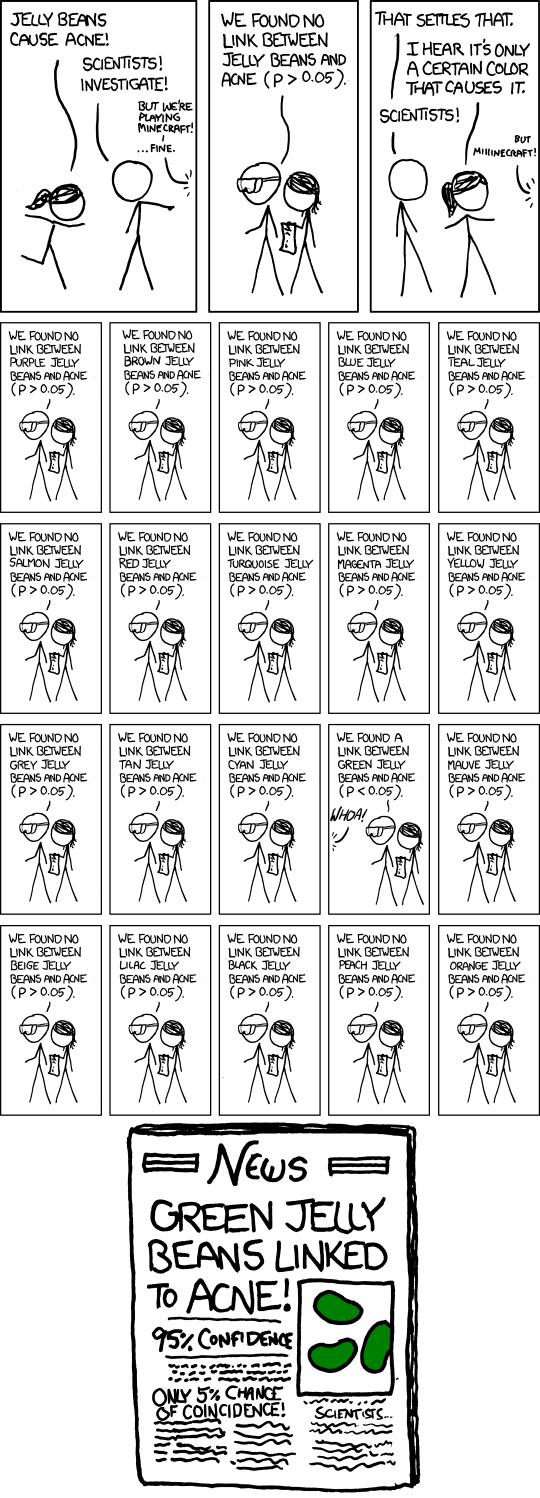

1. Correction of p-values in multiple hypothesis testing

If multiple hypotheses regarding a single data set are tested, the p-values need to be corrected. It is called the multiple comparison problem or multiple comparison fallacy. When we are testing multiple features, the probability that one of these features turns out to be significant, and with a very low p-value, increases with the numbers of parameters we are testing. We need to account for that! This funny cartoon from xkcd illustrates it nicely:

This seems obvious now, but I have witnessed this error in many scientific presentations and publications.

2. Cross-validation

When an apparently significant feature is identified in one data set, to check if it is truly significant it needs to be validated in an independent cohort.

When discovering significant parameters, there must always be a training set and a separate test set for the hypothesis. Furthermore, the cohorts should be designed by a statistician to ensure that they are appropriately matched and powered to support your hypothesis within your intended population.

It is incorrect to optimize a parameter in one data set and report its p-value for this set as significant without having tested the parameter in an independent data set.

The performance will always be overestimated in the training set

Conclusion

These are the two things that stuck in my mind after the coffee-break chat with my friend because I have already encountered these problems in my work before, but there are many more aspects of statistical analysis which can be misinterpreted.

A comprehensive article with multiple examples of use and misuse of statistical methods can be found on InfluentialPoints.com.

On this website the following areas are covered and backed up with extensive references:

- Study & Experimental Design

- Summary statistics

- Distributions & Inferential statistics

- Comparing two samples

- Linear models

I hope this helps. All scientists should be statistics-savvy, also to know what they don’t know and involve a statistician early on in planning the research.

I personally would appreciate being consulted for pathology evaluation and interpretation of studies, because this is my area of expertise. Statistics is not – I need expert assistance.

Comments are closed.